Breaking fundamental laws with behavioral economics

Hello, thank you for taking the time to read my blog post! I am going to be sharing two blog posts today. The first (this post) is going to talk about my research from last week and the second one will share my research from this week.

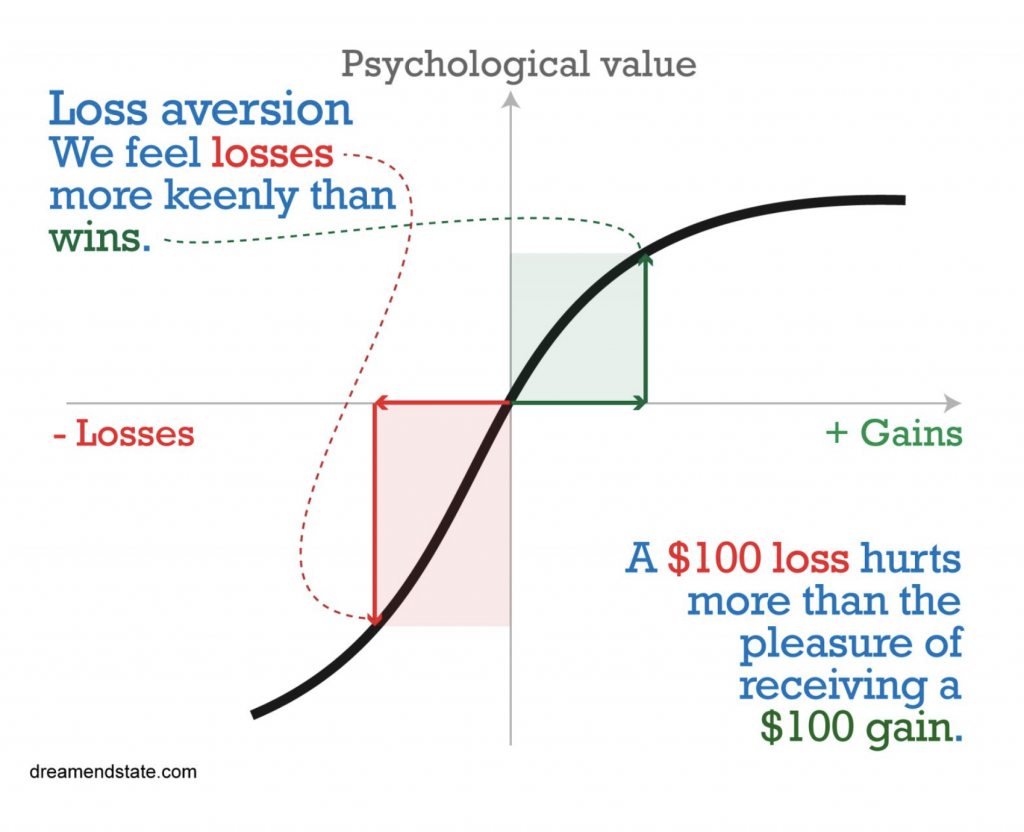

In my second week, I did a lot of research to further my understanding of behavioral economics as a whole and slowly started to investigate sensory marketing. I started my research by watching this crash course video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dqxQ3E1bubI) which taught me a lot of new economical terms like “bounded rationality,” “prospect theory,” and “bubbles” as well as reinforced the ways psychology is incorporated into the field. Prospect theory is the phenomenon that describes how humans hate losing more than they enjoy winning. Behavior economists can see this in a variety of examples. For example, a business ran an experiment to try and incentivize (nudge) its workers to work longer hours. The store found that workers who were given a bonus and told that it would be taken away if they didn’t stay late were much more likely to stay later than workers who were told that they would make the bonus if they stayed late. Simply put, humans hate the thought of losing more than we like the prospect of gaining. Other experiments have been done to model this. In one, a participant was told that they would win $100 if they won a coin toss but would have to pay $50 if they lost. They found that very few participants actually agreed to play, despite the potential reward being much greater than the potential loss. This, of course, differs from person to person and, thus, behavioral economists have started to group participants of this study into two categories: risk-neutral or risk-averse.

I was also introduced to new ways that phrasing and wording effects (Whorf) can affect consumer habits. For example, a packaging label is more appealing to customers if it says “75% fat-free” rather than “25% fat.” In a similar sense lottery’s are more appealing if they inform a consumer that they have a 1/100,000 chance to win rather than a 99,999/100,000 chance of losing. Another psychological phenomenon that I saw was in a study/game called “Animal Spirits.” In the game, there are two participants. At the beginning of the game player 1 is given 100 dollars. With that 100 dollars player 1 must split the money with player 2, yet player 1 has the choice of how to split the money. Player 2 must decide either to accept or decline the trade; if they decline, neither player gets anything, if they accept, each player gets their end of the deal. Through a purely rational lens, it would make sense that player 2 should accept the trade no matter what as any money is better than none, yet studies have found that people are driven by unfairness, injustice, and revenge, which can cloud one’s ability to make the rational decision. All of these examples show how exterior motives and variables oftentimes outweigh/impeded us from making rational decisions, which goes against many classical economics laws which, by definition, are not meant to be broken.

I also began to look at marketing and the ways companies set prices and learned about an experiment that was done with high-quality goods. In the study, participants were given two glasses of the same wine yet they were told that one was $100 and the other was $10. They found that the vast majority of participants preferred the glass that was more expensive despite both being the same. This shows us that for high-quality items, people will actually sometimes prefer a higher price because society has become so entranced to believe that high price = high quality and low price = low quality. This goes against what classical economics tells us which is that customers always prefer the lowest price.

Thank you for taking the time to read this blog post, if you want to learn more… keep on scrolling, more information to come!

So interesting, Gavin! I wonder how the hate of losing vs the love of winning applies to athletes and coaches….

Also, let’s plan to talk about Benjamin Whorf’s theory of linguistic determinism. I think you will find it fascinating.